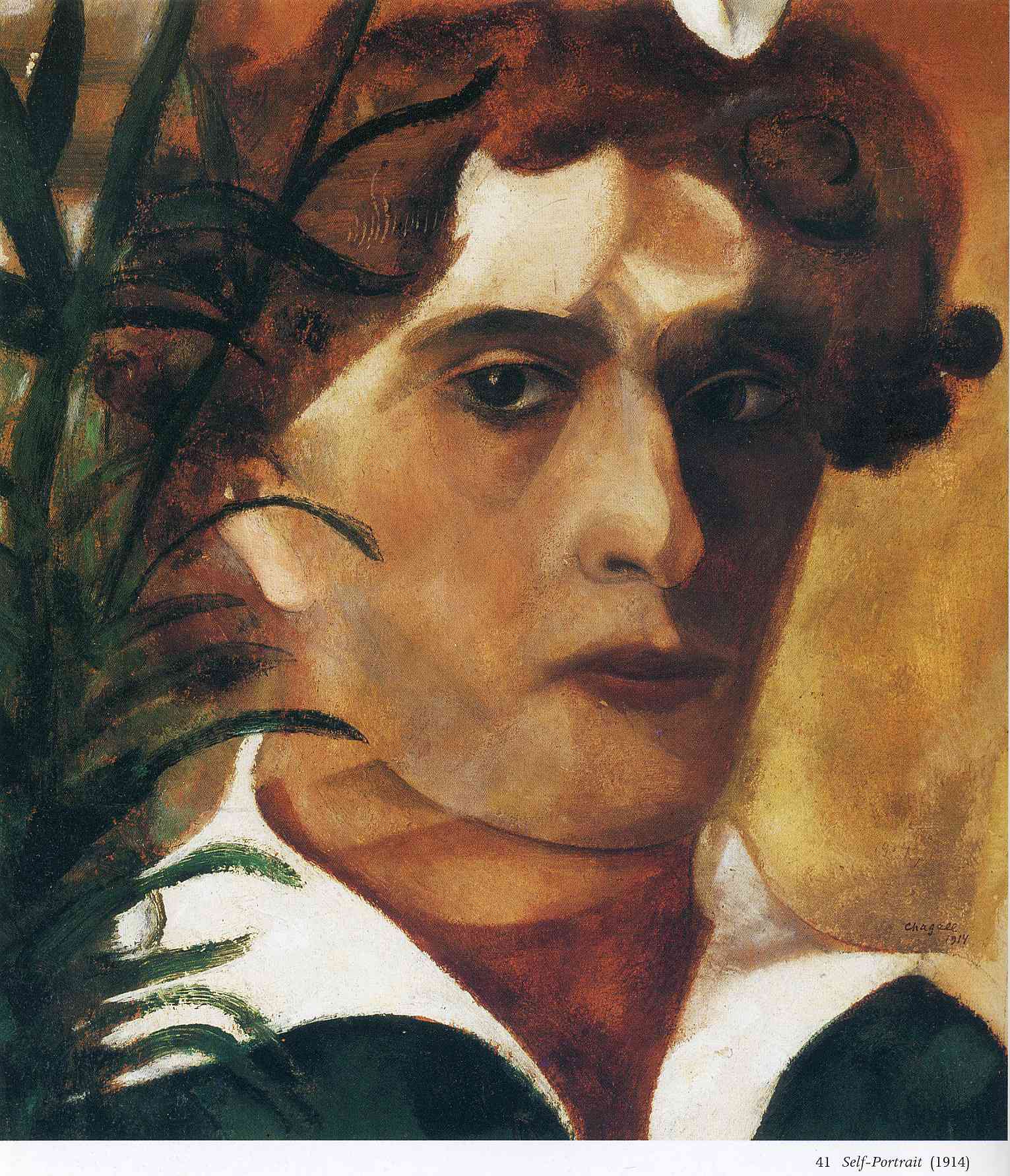

« Je m’appelle Marc, j’ai l’intestin très sensible et pas d’argent, mais on dit que j’ai du talent. »

Marc Chagall – Ma vie

Numerous attributes come to my mind each time my eyes brush against a canvas bearing the indelible Chagall signature, the most prominent of which would certainly be tenderness, and reverie. The timeless charm, a certain childlike naïveté of his depictions combined with the iridescent hue of colours make for a unique experience that touches the soul. Above all that, there is also an element of incomparable seduction and invitation in Chagall, encouraging one in a very intimate engagement with his work through its astounding richness of meaning that offers a plenitude of interpretation. As in a dream one is transported into a world where each colour has its own definite implication and context, where mere shapes tell their own stories, where cultural influence espouses deeper spiritual significance.

Born in 1887 in Vitebsk, the firstborn of nine children, Chagall’s life, like his work, gives the impression of a pilgrim in a constant movement between worlds and between cities, rising from humble origin into a wealthy milieu, traveling the world and yet longing for the warm place of simplicity and familiarity that is so strikingly evident mainly in his touching depiction of village life where family, religion, nature and music are closely interconnected. A child of a devoted Jewish family, his decision to embark on an artist’s path was definitely not without obstacles, but a steady flow of artistic output that followed his starting point at the studio of Yehuda Penn in 1906 shows a man wholeheartedly devoted to a vocation that he with the same characteristic charm reflected also in his paintings made entirely his own.

« Muni de mes vingt-sept roubles, les seuls que j’aie reçus de mon père, dans ma vie (pour mon enseignement artistique), je m’enfuis, toujours rose et frisé, à Petersbourg, suivi de mon camarade. C’était décidé. »

Marc Chagall – Ma Vie

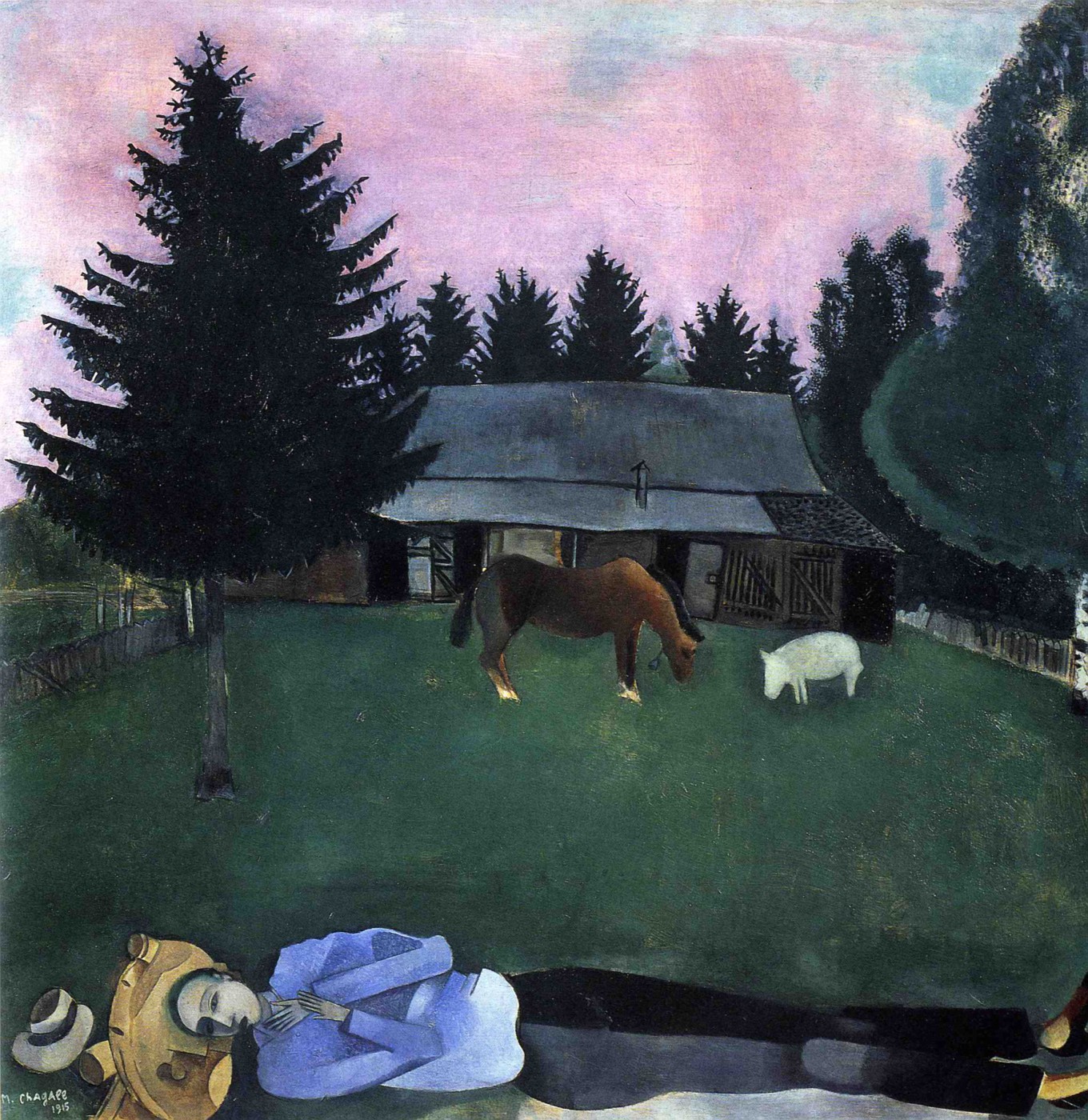

As I was able to follow Chagall’s life through his artwork thanks to a beautifully arranged biography of the Taschen painters edition, I felt as though I were entering a world where even time itself pauses to take a deep breath in its wild race towards eternity, where the only thing that matters is to watch with eyes and heart wide open to fully perceive the beauty, the depth of the moment captured with both intensity and gentleness that the painter offers, as if he were giving each of his paintings a life of its own. One of the most suggestive examples of this realm of peaceful quiet and halted time I found in the Le Poète allongé, whose relatively restrained and subdued hues endow the scenery with an air of fragility and profound calmness spreading like a blanket over the poet’s dream, and the painting seems as though knitted from the melody of the famous Schumann Träumerei. I don’t think it would be very far from truth to say that one almost feels invited into the poet’s dream, a dream that remains thus locked in one’s imagination yet becomes an integral part of the whole experience this painting evokes.

« J’ouvrais seulement la fenêtre de ma chambre et l’air bleu, l’amour et les fleurs pénétraient avec elle. Toute vêtue de blanc ou tout en noir, elle survole depuis longtemps à travers mes toiles, guidant mon art. »

Marc Chagall – Ma vie

Another theme pervading Chagall’s work like the scent of cherry blossoms is the one inspired by his great love for his fiancée and later his first spouse Bella Rosenfeld, the daughter of a wealthy jeweler, whom he married in 1915 – an event resulting in L’Anniversaire, a deeply touching testimony to the purity of the couple’s love where the tenderly kissing pair, the cozy room evoking the glow of a newfound happiness, the village behind the window and the little bouquet in Bella’s hands make one the privileged witness of a very personal moment. Accordingly, an apt choice of colours accompanies this scene of marital bliss where the bolder tones of red emanating warmth are finely balanced with the cooling shades of black, grey, white and blue. What fascinates me particularly about this painting is the great emphasis on an exquisite work of detail like that of the embroidered tapestry in the background, and the table with objects of daily usage, bringing to the picture also the pleasurable, earthy presence of the quotidian as a pillar of solidity amidst this fluttering, amorous dream.

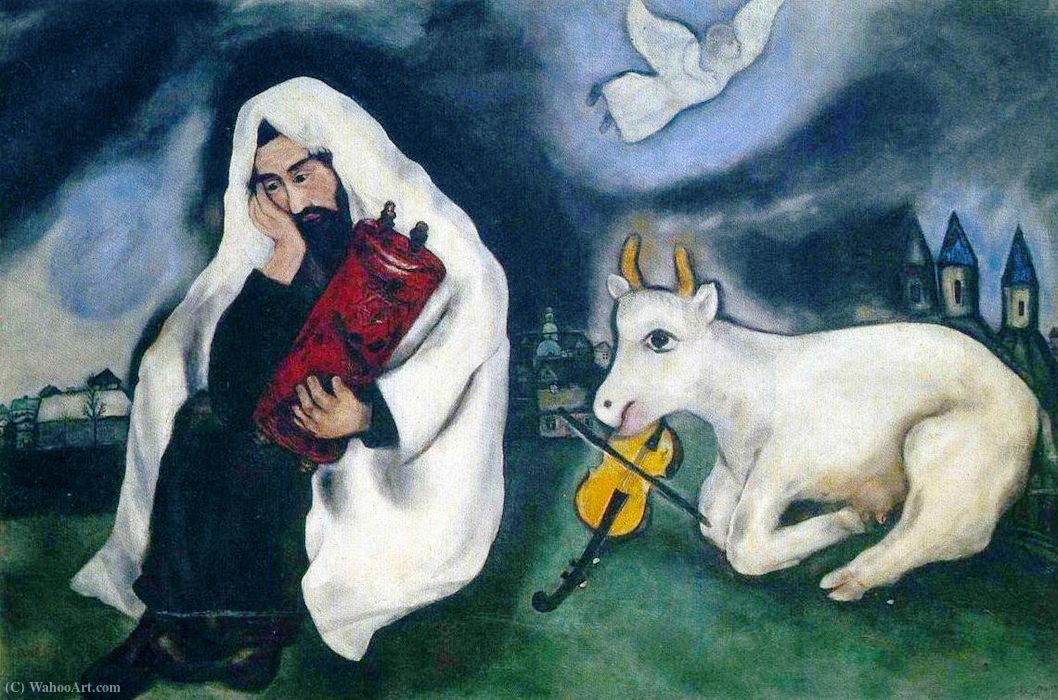

« L’essentiel, c’est l’art, la peinture, une peinture différente de celle que tout le monde fait. Mais laquelle ? Dieu, ou je ne sais plus qui, me donnera-t-il la force de pouvoir souffler dans mes toiles mon soupir, soupir de la prière et de la tristesse, la prière du salut, de la renaissance ? »

Marc Chagall – Ma vie

The third major object of the painter’s brush is not merely a religion clothed in Chagall’s unique perception of colour and concept; the spiritual dimension which the painter so generously bestows upon majority of his artworks with Judeo-Christian motives entails also all the tragedy, loneliness and suffering stemming from a deep devotion to the word of God which many a spiritual person encounters in life. In his paintings, the reality of suffering being inseparable from a life of faith comes in repeated patterns, as though the very history of the Israelites and their tribulations across the centuries were the core of Chagall’s principal inspiration. Just like in Le Juif en prière, his painting of a solitary Jew in Solitude holding a roll of Torah firmly in his hands while absorbed in pensive melancholy reveals much of the pain of those loyal to their ethnoreligious background, and also grimly and eerily foretells all the terrors to come during the Second World War.

« Mais mon art, pensais-je, est peut-être un art insensé, un mercure flamboyant, une âme bleue, jaillissant sur mes toiles. »

Marc Chagall – Ma vie

Chagall’s pallette is not only bursting with a whole array of tonal progression, making one highly susceptible to each slight shift of mood in his paintings, but it also offers a unique walk down the memory lane into the innocent days of childhood where the simple joys of everyday existence were a pretext enough for merry celebration, like in Le Violoniste where an old musician with a young beggar boy by his side share the extatic moment of a freshly married couple standing timidly in the background, as though abashed by the very magnitude of their own happiness – not merely a depiction of a Jewish wedding, but also a passionate celebration of life in its unstoppable cycle of constant rebirth, the rebirth of love and hope, underlined by the choice of earthy tones evoking the certitude of repetition.

As it is the case with all great artists, Chagall’s work and life are united in an intimate relationship where the one mirrors the other with much ebullience, sensitivity and deep reflection to a degree when it is no longer possible to retell the painter’s biography without a careful and attentive study of his magnificent, multi-faceted paintings full of playful hints and allusions, chromatic gradation and deep love above all; love towards the world with all its sorrows and towards art itself, for it is art that serves as a saving rope which connects the world of emotion with the world of reality and helps to sustain the latter by expressing, expanding and nurturing, with loving care, the former.