The glow of the stones warmed Lily’s veins like wine. More completely than any other expression of wealth they symbolized the life she longed to lead, the life of fastidious aloofness and refinement in which every detail should have the finish of a jewel, and the whole form a harmonious setting to her own jewel-like rareness.

Edith Wharton – The House of Mirth

“I shall always tell you,” her aunt answered, “whenever I see you taking what seems to me too much liberty.”

Henry James – The Portrait of a Lady

“Pray do; but I don’t say I shall always think your remonstrance just.”

“Very likely not. You’re too fond of your own ways.”

“Yes, I think I’m very fond of them. But I always want to know the things one shouldn’t do.”

“So as to do them?” asked her aunt.

“So as to choose,” said Isabel.

A common thread runs through the long list of works of world literature now established securely with the label of a classic, effectively joining them into a string of brilliant minds that successively climbed the ladder of fame and left their mark of influence. It is the mirror which they courageously put before a bewildered audience of their era, becoming a reflection of their habits and morals in the most cohesive, incisive and shameless of ways so as to paint a vivid portrayal of an age that had its sway in the precarious currents of history.

The accolades of a keen wit combined with insight and a piercing eye could not possibly be distributed more readily and more deservedly when it comes to two magnificent minds of the 19th century whose virtuosity of pen and accuracy of observation reconstructed in the greatest minutiae the dazzling world of the Gilded Age (drawing a parallel line to the European La Belle Époque), spreading a force of impact and meaning as far as the shores of the 21st century when the voices of Edith Wharton and Henry James still sound far down the winding lanes of our brash and cynical times with much the same clarity and resonance as those 150 years ago.

Having been swept off of my feet by the beauty and sophistication of Edith Wharton’s exquisite command of language already a long time ago, it has been only a few months since I finally succeeded in adding also her faithful friend and fellow writer of the same epoch, Henry James, to the reading schedule, and to say that I was delighted would definitely be a huge understatement of the admiration and awe I felt when reading James’s highly intellectual prose which lacked none of Wharton’s shrewdness and intricacy embalmed in soft layers of poetic tendencies, thus making the utmost demands on the full presence and alertness of one’s brain while also providing the reader with a delight of a truly unique kind.

If I were to stress and vindicate the importance of the appeal which the voluminous work of these two genius minds engenders, I would certainly delve deeper into the two dominant facets presented by Wharton and James with such elegance that one almost forgets what a genuine tragedy creeps beneath the delicious veneer of their lustrous writing skills – marriage and society.

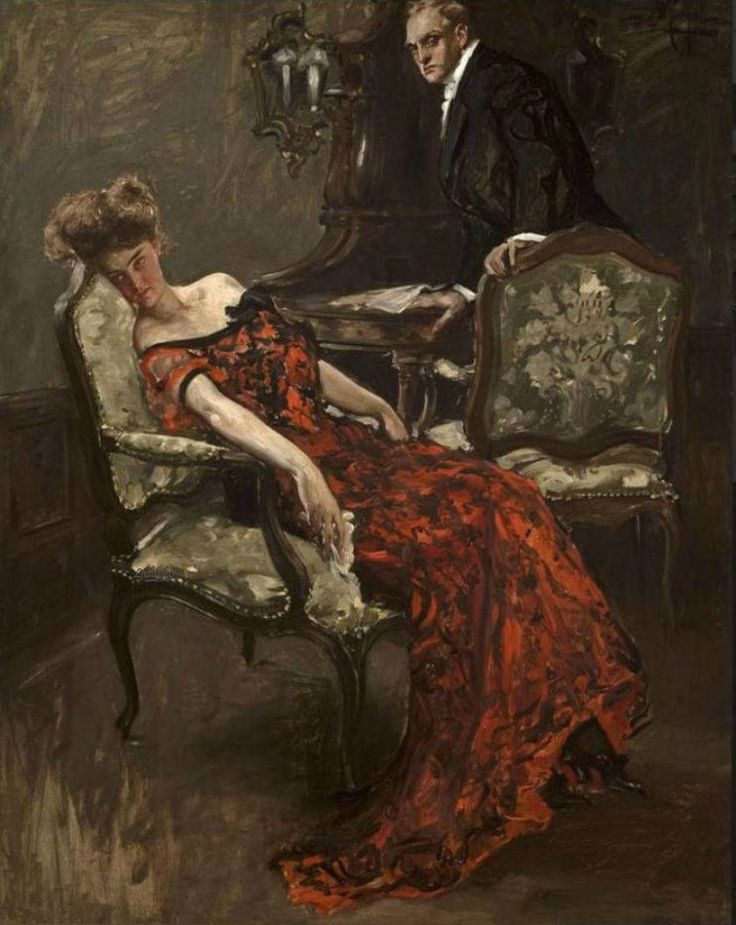

The world of James’s and Wharton’s characters can be without a doubt likened to a gilded cage with delicately shaped, iron-tight bars. It is a habitat of a society that doesn’t pardon a step out of the rigid, widely accepted norms; a society where money is the Bible and reputation the Altar of Holiness. Marriage is limited to a mutually advantageous market-trade business where sincerity counts for little and love is an unforgivable sin leading to eternal damnation, a superfluous weakness. This world is a guillotine made by the proper hands of its victim, a theatre with a polished mise-en-scène designed to be merely admired and longed for, lacking any logic of purpose. Everything has the air of a play that starts as a light-hearted farce only to end in a sudden twist of sorrowful bitterness. An ever repeating scenario unfolds in front of the eyes of the bedazzled spectator – the actors know they are playing their own tragedy, but putting on a formidable performance ultimately becomes more important than the inevitable consequences of it. They are absorbed in the brilliancy of their dialogue without the need to think about its meaning, they slide on the surface and carefully avoid probing the depth.

In such a world, a woman’s worth is derived from the loveliness of her face and the outward gracefulness of her manners, from her stainless reputation artfully masking an artificially constructed lie. The impeccable trimming of her dress accordingly dictates the corset-tight routine of her life – a life where every detail, every movement, every word, breath, glance and gesture has to fit with the same punctuality as the placement of the delicate lace on her fashionable gown, has to be measured with the coup d‘œil of a skilled general arranging his forces for a tough battle. Eyes are everywhere – watching, prying, unforgiving, waiting eagerly for the slightest sign of faltering to turn into famished hyenas ready to tear their prey into pieces and adorn themselves with its remains.

Reading Edith Wharton‘s three major novels – The House of Mirth, The Custom of the Country and The Age of Innocence (the latter of which brought the authoress a Pulitzer Prize) – is akin to taking a long walk down the Fifth Avenue in the dim gaslight of evening street lamps with the rattle of carriages and the pearly laughter of the ladies haunting the place like a trapped ghost. Her wealthy high society of Old New York is depicted with a grim charm that leaves one spell-bound and horrified at the same time due to the sparkling beauty of the form mixed in equal doses with the cold-blooded tragedy of the content.

The main target of Wharton’s penetrating critique becomes, unsurprisingly, the position of a woman within a society, and the dilemma of a marriage of convention as opposed to a marriage of love. The questions raised by Wharton’s prose I find not merely intriguing, but of most acute importance to the reader of the present day when the steady decline in numbers of married couples is influenced by the very same – if not even more marked – cynicism and skepticism as that reigning supreme during Wharton’s times, reducing the institution of marriage to a business affair that had little to do with feelings, let alone a higher, spiritual purpose.

Another trait typical to Wharton’s characters is a miserable fight against their own instincts and the prejudice of their world with which they retain a poisonous love-hate relationship, a world which holds them captive. The chains are of scented satin and silk, and its vulgar beauty sucks their soul and life invisibly out of them while giving them the impression of having the best time of their lives. They are like flies that landed in a bowl full of honey, and a sweet, slow, suffocating death awaits them. That is the utmost tragedy of their superficial, glittery lives – they love money, and they eventually drown in its vast sea, or end up washed upon the shores of poverty and emptiness.

Wharton’s characters are the fine contours that shape this gilded cage, so masterfully and ironically depicted in her novels. They passionately long for a different life, but their personal tragedy lies in their incapability to live anywhere outside a stucco decorated drawing room that reflects their own glamour. They are simply not able to adapt and come to terms with anything less than the standard with which they were once inoculated. When finding themselves anywhere beyond the stylish circle of their world of meretricious luxury, they turn into a fish removed from its natural environment nervously gasping for air, and in the end they decide that the vision of a change is more satisfactory than the dangerous risks they would have to undertake in order to turn it into reality.

It is usually too late when they realize that the demon of material possession cannot satisfy their hunger for the depth of a meaningful and useful life, or, as in The Custom of the Country, which I found the most blood-chilling of all three novels and almost too heart-breaking to finish, they do not arrive at that revelation at all, even after causing a tremendous collateral damage.

In the case of Henry James‘s awe-inspiring portrait of words – The Portrait of a Lady, a wholly different polemics unfolds amidst the set of common themes of the very same milieu which Wharton with a tasteful irony deprived of its illusional innocence. In this timeless classic, James decided to take a close look at a life of a young, intelligent woman endowed with purpose, ideas and ambition, and scrutinize it under the magnifying glass of independence and inheritance that hugely influence all the major decisions of the passionate and high-spirited Isabel Archer.

Themes highly relevant for the confused age we live in pervade James’s story through and through. Where Wharton’s heroines blatantly hunt for a rich husband to use who will secure them with a position within the poisonous circle of their equally rich acquaintances, in James’s novel we witness repeatedly how Isabel Archer stubbornly adheres to her idea of perfect independence to the point of being so blinded by its glow that she desperately gropes about in an attempt to steady her balance, and in that moment of perplexed sensations she grabs the very thing which will prove to be her finest undoing. Her initial fear of the imposing burdens brought along by the convention of commitment and love, and her outright refusal of a devoted man’s heart which comes in a recurrent pattern on multiple occasions eventually lead her to a place where she is forced to admit, though still but unwillingly through the lens of a wounded pride, that she traded permanence, stability, safety and loyalty for the exhilarating taste of the new, exotic and momentary, and she sees her young life running through her fingers in trickles of treacherous quicksand.

One does not have to look far for evidence how the progressive destruction of family is bringing about the inevitable decay of society as a whole since its most essential nucleus existing and supporting it from times immemorable is being dismantled and scorned. It is why I think that all the themes presented by James and Wharton in their masterworks – the social problems and the cobweb of interpersonal relationships, the true, hideous face of material craze and the importance of a marriage built upon mutual sincerity, loyalty and devotion – are as crucial for the present reader as ever before, providing an unparalleled clarity of insight and great wisdom that is offered to be applied as a remedy to the malady of cynicism that burrowed its claws into the neck of our times, if only we were willing enough to take responsibility and make use of it.