“Criez de joie pour le Seigneur, vous qui lui obéissez. Pour ceux qui ont le coeur pur, il est bon de chanter sa louange. Remerciez le Seigneur avec la cithare, jouez pour lui sur la harpe à dix cordes. Chantez pour lui un chant nouveau, rythmez bien vos cris de joie avec tous vos intruments.” Voilà comme l’un de plus grands poètes et rois de l’histoire chante et professe, avec une passion presque bouleversante, son amour intime et profond pour son Dieu. La musique prend une place prépondérante dans les Psaumes de David, suscitant et élevant la conception de la prière vers une dimension entièrement nouvelle et différente où l’intégration de l’Absolu ne se passe que grâce à la musique.

J’ai toujours pensé que l’expérience humaine avec cet unique art de la communication qui est la musique fût l’une de plus révélatrices, même métaphysiques, qu’on peut éprouver – pas seulement à cause de la force et la douceur de l’absorption dans le moment quand on l’écoute, entrant un univers tout imprévu et mystérieux, mais aussi à cause de se trouver comme un témoin de la réunion de toutes les parties les plus essentielles qui constituent la vie même.

Ayant croisée une écriture exquise sur l’évolution de la mélodie et sa signification au fil des siècles dans une collection d’essais de Milan Kundera, Les testaments trahis, elle m’a fait réflechir sur cette diversité que la mélodie offre – parfois cachée dans la structure solide du contrepoint comme un pilier de stabilité d’un morceau tout en ne revendiquant pas une place strictement individuelle et dominante dans le cadre de la composition, parfois souple comme l’air, respirant et s’élevant au-dessus des autres voix, guidant notre âme dans un temple délicat de l’introspection tranquille.

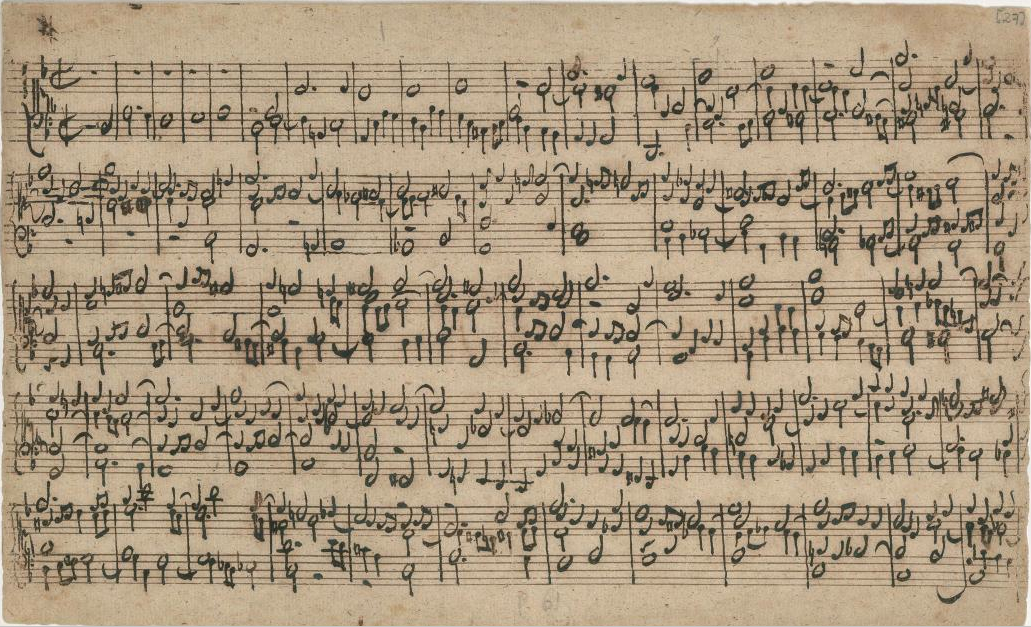

Il me semble que l’art de la mélodie, jusqu’à Bach, gardera ce caractère que lui ont imprimé les premiers polyphonistes. J’écoute l’adagio du concerto de Bach pour violon en mi majeur : comme une sorte de cantus firmus, l’orchestre (les violencelles) joue un thème très simple, facilement mémorisable et qui se répète maintes fois, tandis que la mélodie du violon (et c’est là que se concerne le défi mélodique du compositeur) plane au-dessus, incomparablement plus longue, plus changeante, plus riche que cantus firmus d’orchestre (auquel elle est pourtant subordonné), belle, envoûtante mais insaisissable, immémorisable, et pour nous, enfants de la deuxième mi-temps, sublimement archaïque.

La situation change à l’aube du classicisme. La composition perd son caratère polyphonique ; dans la sonorité des harmonies d’accompagnement, l’autonomie des différentes voix particulières se perd, et elle se perd d’autant plus que la grande nouveauté de la deuxième mi-temps, l’orchestre symphonique et sa pâte sonore, gagne de l’importance ; la mélodie, qui était “secondaire”, “subordonnée”, devient l’idée première de la composition et domine la structure musicale qui s’est d’ailleurs transformée entièrement.

Alors change aussi le caratère de la mélodie : ce n’est plus cette longue ligne qui traverse tout le morceau ; elle est réductible à une formule de quelques mesures, formule très expressive, concentrée, donc facilement mémorisable, capable de saisir (ou de provoquer) une émotion immédiate (s’impose ainsi à la musique, plus que jamais, une grande tâche sémantique : capter et “définir” musicalement toutes les émotions et leurs nuances). Voilà pourquoi le public applique le terme de “grand mélodiste” aux compositeurs de la deuxième mi-temps, à un Mozart, à un Chopin, mais rarement à Bach ou à Vivaldi et encore moins à Josquin des Prés ou à Palestrina : l’idée courante aujourd’hui de ce qu’est la mélodie (de ce qu’est la belle mélodie) a été formée par l’esthétique née avec le classicisme.

Pourtant, il n’est pas vrai que Bach soit moins mélodique que Mozart ; seulement, sa mélodie est différente. L’Art de la fugue : le thème fameux est ce le noyau à partir duquel (comme l’a dit Schönberg) le tout est créé ; mais là n’est pas le trésor mélodique de L’Art de la fugue ; il est dans toutes ces mélodies qui s’élèvent de ce thème, et font son contrepoint. J’aime beaucoup l’orchestration et l’interprétation de Hermann Scherchen ; par exemple, la quatrième fugue simple ; il la fait jouer deux fois plus lentement qu’il n’est coutume (Bach n’a pas prescrit les tempi) ; d’emblée, dans cette lenteur, toute l’insoupçonnée beauté mélodique se dévoile. Cette remélodisation de Bach n’a rien à voir avec une romantisation (pas de rubato, pas d’accords ajoutés, chez Scherchen) ; ce que j’entends, c’est la mélodie (un enchevêtrement de mélodies) qui m’ensorcelle par son ineffable sérénité. Impossible de l’entendre sans grande émotion. Mais c’est une émotion essentiellement différente de celle éveillée par un nocturne de Chopin.

Comme si, derrière l’art de la mélodie, deux intentionnalités possibles, opposées l’une à l’autre, se cachaient : comme si une fugue de Bach, en nous faisant contempler une beauté extrasubjective de l’être, voulait nous faire oublier nos états d’âme, nos passions et chagrins, nous-mêmes ; et, au contraire, comme si la mélodie romantique voulait nous faire plonger dans nous-mêmes, nous faire ressentir notre moi avec une terrible intensité et nous faire oublier tout ce qui se trouve en dehors.

Milan Kundera – Les testaments trahis